VIDEO | BAFT CEO: Charting the course for transaction banking in a fractured world

Tod Burwell

Jun 06, 2025

Carter Hoffman

Apr 10, 2025

Carter Hoffman

Apr 10, 2025

In ports and boardrooms around the world, patterns of commerce that once seemed immutable are shifting with the geopolitical tides.

Wares that a decade ago would travel directly from Shanghai to Los Angeles now make telling detours before reaching their final destination. These midway points are part of a new cohort of “connector” trade nations linking East and West.

In this article, we will explore the rise of these intermediary nations and the forces reshaping trade routes. We will then look in detail at four unique case studies of connector nations in action before moving on to discuss the benefits and drawbacks of this new order of trade flows. Lastly, we will explore some policy considerations that crop in a connector-filled world before concluding with a brief discourse into what may lie in the years ahead.

Not long ago, global trade was dominated by straightforward routes. Goods, often designed in the technologically more advanced West, would travel directly from manufacturing giants like China back to the dominant consumer markets in the US or Europe.

Things aren’t quite so straightforward anymore.

Connector trade nations are those countries that act as a kind of mid-station between trading partners that previously traded directly, taking in goods, adding some value, or simply repackaging them, and then exporting them onwards.

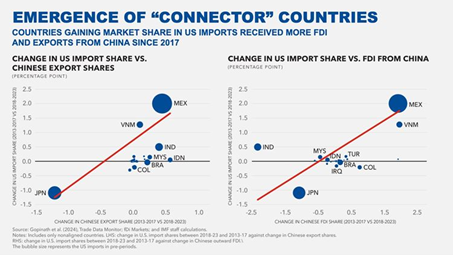

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has observed an emergence of connector nations since 2017, particularly between the USA and China, with greater Chinese exports or investments in a third country tending to be associated with increased exports from that country to the US.

These connector economies are often, though not always, non-aligned to either side of the big-power rivalries, which allows them to trade freely with both sides without angering a key ally. These nations seem to have been able to profit from global tension by picking up business that used to occur bilaterally.

For example, when the US imposed tariffs on Chinese products under the first Trump administration, many American importers turned to Vietnam for supply. In turn, Vietnam’s factories (some of which are Chinese-owned) imported more components from China to meet the newly growing US demand in Vietnam.

These connectors have, to some extent, cushioned the impact of geopolitical rifts on trade. For instance, between 2018 and 2023, amid the opening salvos of Trump’s trade war with China, direct US imports from its Asian rival fell by around 20%, while indirect trade via other countries – perhaps most notably Mexico and Vietnam – increased over the same time period. US imports from Mexico grew by around 38% over these years (surpasing China as the USAs largest trading partner), and US imports from Vietnam grew by around 177%. Likewise, Chinese exports to Mexico grew by around 85%, and Chinese exports to Vietnam grew by around 64%.

While they cushion the short-term economic impact of geopolitical shocks, the emergence of these connector-based trade profiles does not equate to true trade diversification, since many connector nations remain deeply linked to the same dominant supplier (often China) for inputs. Further, this version of changing trade patterns can seem to undermine the geopolitical influence of governments to control their trade flows. Regaining this influence is perhaps one of the reasons for President Trump’s campaign rhetoric of blanket tariffs being placed on all US imports.

As we’ll see, this paradox – where connectors provide an alternate path but not a fundamentally different basket of eggs – lies at the heart of both the promise and peril of relying on them.

Geopolitical fragmentation is not limited to the US and China. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and the ensuing Western sanctions on Moscow, direct trade between Russia and the West collapsed almost overnight. In its place, however, Russian commerce deepened with many non-sanctioning countries.

For instance, Türkiye and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) experienced a surge in trade with Russia as they became conduits for goods and finance that could no longer flow directly from the West. Russian trade with these countries increased at respective annualised rates of 20.8% and 23.5% between 2018 and 2023. Likewise, India increased its purchasing of heavily discounted Russian crude oil and then exported record volumes of refined fuels (like diesel or jet fuel) to Europe.

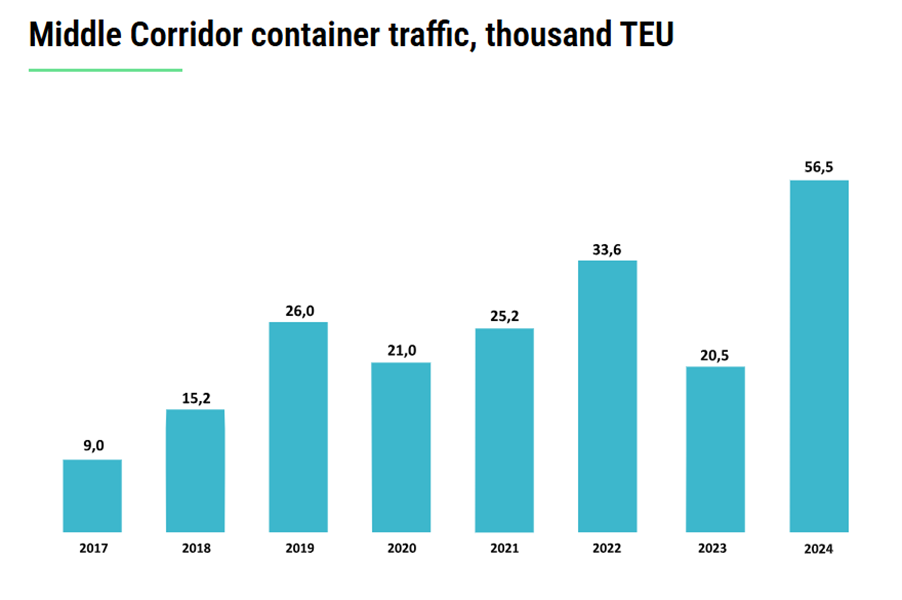

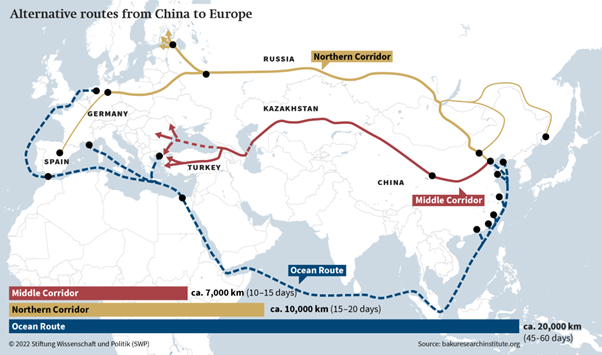

Meanwhile, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has been literally paving new trade routes across Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. By investing in transportation infrastructure like ports, railways, and highways along key routes, China is creating alternative corridors to diversify away from traditional chokepoints. When war made the Eurasian rail route via Russia less appealing, attention turned to the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR), which has been dubbed “The Middle Corridor”. Container traffic on this route spiked by 33% in 2022 as firms sought to bypass Russia. Infrastructure bottlenecks caused some retrenchment in 2023, but volumes accelerated again in 2024.

Many of the emerging connector economies are located at strategic crossroads of these new corridors. Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, and Türkiye, for example, are located on the overland route linking China to Europe, while maritime hubs like Singapore and Djibouti sit along the BRI sea lanes.

Bilateral and regional trade pacts that secure market access are another driver in the emergence of connector economies. Vietnam, for instance, benefits from trade deals with partners on all sides. It’s in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) with China, has an FTA with the EU, and (at least for now) enjoys access to the US market via its low-cost advantage.

The data are starting to show a subtle change in the composition of trade volume. World exports of intermediate goods – an indicator of complex supply chains – fell 5% in 2023 (the latest year the WTO report is available). This dip might indicate production becoming somewhat more regional or simplified, a possible effect of both geopolitics and firms trimming their risk, following the lessons of the COVID-19 pandemic.

For better or worse, connector nations are here, which makes it important for businesses and policymakers alike to understand where this can be a benefit and where it might pose some challenges.

By routing trade through intermediary countries, companies have been able to sidestep tariffs and trade barriers, retain access to critical markets, and diversify their logistics.

For example, an American retailer facing 25% tariffs on Chinese-made furniture might import similar wares from Malaysia or Vietnam instead, benefiting from lower (or no) duties. In turn, that connector nation gains jobs, investment, and tax revenue as global supply chains re-anchor on its shores. Indeed, many have seen infrastructure upgrades and technology transfer as multinationals set up operations within their borders.

Many connectors have also enjoyed export booms. Vietnam’s exports to the EU and particularly the US have risen sharply since 2016 as it absorbed manufacturing that might otherwise have stayed in China.

| Vietnam Exports to: | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

| EU ($ billion) | 41.7 | 45.1 | 44.7 | 39.4 | 45.5 | 53.5 |

| USA ($ billion) | 41.5 | 47.6 | 61.4 | 77.1 | 96.3 | 109 |

The existence of connectors can also add a layer of resilience to global supply chains by providing the alternate routes that help the global system adapt to shocks. The presence of connector-mediated channels meant that when direct US-China trade was disrupted, American factories could still get parts (albeit via a longer journey) and Chinese producers could still reach customers.

A foremost concern is that these arrangements might be fragile or temporary if geopolitical tensions worsen. Policymakers could crack down on trade routed through third parties, viewing it as sanction- or tariff-dodging. Governments are already showing such instincts: in 2024, India imposed tariffs on certain steel imports from Vietnam, explicitly aiming to disrupt Chinese steel being transshipped under a Vietnamese label. Likewise, the rhetoric from the beginning of President Trump’s second term seems to indicate that more comprehensive trade barriers may be on the horizon.

From a supply chain perspective, using a connector doesn’t eliminate the root concentration risk – it often just shifts it. A company still ultimately depends on, say, Chinese electronics parts; those parts just arrive through an intermediary. Should a crisis hit the primary source, connector routes would offer limited consolation. This illusion of diversification can breed complacency unless firms dig into where inputs are truly originating.

Even in the absence of escalations or shocks, connectors themselves are liable to face capacity and governance challenges, especially in the early stages of their new role. A sudden influx of trade and investment can strain a country’s ports, roads, and customs systems. We saw this when the Middle Corridor through Central Asia overflowed with rerouted cargo; delays spiked as infrastructure reached its limits which led to a sharp decline in shipping volumes in 2023. Connector nations must therefore be able to rapidly scale up their infrastructure and efficiencies to handle their newfound role. Those with high logistics performance and efficient customs procedures tend to handle the connector role better. Others risk becoming bottlenecks if they fail to keep up.

There is also the risk of domestic instability or policy missteps. For instance, an overvalued currency or political unrest in a connector country could disrupt the very trade flows it is meant to facilitate, leaving businesses relying on that route scrambling. Connectors often lack the full robustness of larger economies, making them vulnerable to shocks or overdependence on a few sectors.

Diplomacy is another challenge. By definition, connector countries maintain ties with rival powers, which can be tricky if tensions escalate. If forced to choose sides on an issue like sanctions or security, a connector could alienate one bloc or the other, creating volatile policy environments for companies operating there.

Take Türkiye for example. It has profited by staying open to both Western and Russian business, but as a NATO member, it faces pressure to align with Western sanctions. Its balancing act introduces geopolitical risk to firms using Türkiye as a conduit. Similarly, Vietnam must manage its booming economic links with both China (its top import source) and the US (a top export market), all while the US eyes Vietnam’s currency practices and trade surplus with scrutiny.

A decade ago, Vietnam was a relatively small player in global trade. A year ago, it was a textbook example of a connector nation on the rise. Today, its very success as a connector may be undermining its ability to continue in this role.

When the US-China trade war began in 2018, Vietnam positioned itself as a manufacturing hub between China and Western markets. Western multinational companies, from electronics to apparel, ramped up investments in Vietnam, attracted by its low wages, improving infrastructure, and, crucially, its political posture of being friendly to all sides. Chinese firms also set up operations there, thanks to deepening relations between the two countries, using Vietnam as an export base to avoid tariffs.

As a result, China’s exports to Vietnam surged 64% from 2018 to 2023, while US imports from Vietnam rose by 132% in the same period. In other words, Vietnam became a conduit for goods ultimately destined for the US and Europe, even as direct China-US trade stagnated.

By 2024, Vietnam had the third-largest goods trade surplus with the United States of any country, behind only China and Mexico. The US trade deficit with Vietnam topped $110 billion in the first eleven months of 2024, up nearly 18% from the previous year. For Vietnam, this export boom has been an economic boon – creating millions of jobs and making it one of the fastest-growing economies in Asia. Hanoi also managed to sign an array of trade deals (including one with the EU) and largely managed to keep relations smooth with both Washington and Beijing.

Its this very success, however, that may now be Vietnam’s greatest threat. A Political Risk Report from Marsh, an insurance broker and risk advisor, notes that “As one of the largest recipients of Chinese foreign direct investment and imports in recent years, Vietnam may be among the first connectors to face more trade barriers if further fragmentation occurs.” Indeed, in 2024, India imposed tariffs on Vietnamese steel that was suspected to be just repackaged Chinese steel.

US officials, too, monitor Vietnam’s currency and trade practices; the US Treasury has at times put Vietnam on watch for possible currency manipulation to keep its exports competitive. If US-China decoupling intensifies, as Trump’s rhetoric and actions indicate that it will, Vietnam could face pressure to clamp down on Chinese transshipments.

For now, Vietnam is betting that it can maintain a careful balance and continue to be an essential link in global supply chains.

On the other side of the world, Mexico is another successful connector economy, that has entered the US administration’s crosshairs.

Mexico shares a long border with the United States and has been a joint member of the world’s largest free trade area (first NAFTA and now the USMCA) alongside the USA and Canada since 1994.

Traditionally, Mexico’s manufacturing sector has been highly integrated with the US (autos, appliances, etc.), but in recent years it’s also become a backdoor for Asian exports. Facing US tariffs and political pressure, some Chinese companies began investing in factories in Mexico – essentially to produce “in Mexico” and then send goods duty-free into the US, exploiting Mexico’s trade access. This kind of vertical connector model (Chinese capital + Mexican labour + US market) is attractive on paper and is seen in sectors like electronics and even automobiles. By 2023, Mexico benefited so much from supply chain rerouting that it surpassed China to become America’s top trading partner.

Reenter President Trump.

With a protectionist president back in the White House, Mexico’s entire trading ecosystem, including its connector model, is under threat. According to the Marsh Political Risk Report, “An early push by the new US administration to renegotiate the USMCA prior to the scheduled 2026 review may strain Mexico’s relations with the US. Investors are also concerned over recent judicial and regulatory reforms.”

If the US President follows through on the tariff threats or reduces Mexico’s trading advantages under USMCA, the country may need to explore new uses for its large industrial base and US-market-focused workforce, and it would almost certainly no longer be an attractive connector country.

Türkiye has long been a cultural and (quite literally, in the case of the Bosphorus bridges) a physical bridge between East and West.

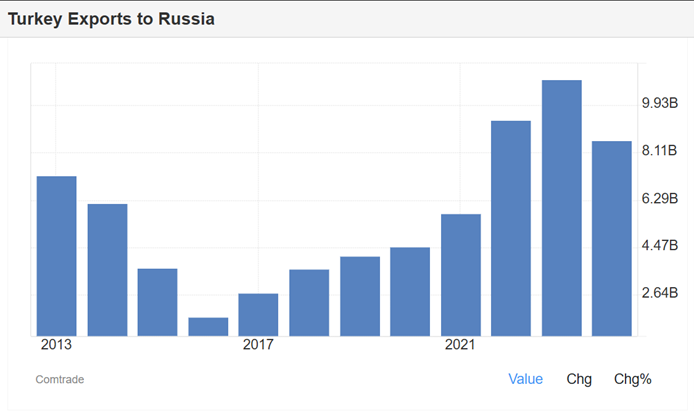

Türkiye is a NATO member with EU customs union ties on one hand, and a neighbour to Russia and part of China’s Belt and Road corridors on the other, a unique positioning turned Türkiye into a key connector when Russia was sanctioned by the West following the invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Turkish exports to Russia surged 62% between 2021 and 2022 as Turkish firms (and likely some EU goods re-exported) filled gaps left by departing Western companies. Istanbul’s banks and bazaars became transit points for everything from electronics to jewels headed into Moscow.

Source: https://tradingeconomics.com/Türkiye/exports/russia

At the same time, Türkiye remains a major overland route for goods moving between Europe and Asia, including Chinese freight trains ending their journey at Istanbul’s ports. Economically, Türkiye benefits from connector status through transit fees, booming trade volumes, and strategic investment (China has invested in Turkish infrastructure; Russia in Türkiye’s energy). Its geopolitical leverage has arguably grown – for instance, Türkiye brokered deals like the (since terminated) 2022 Black Sea grain corridor to keep food trade flowing amid the Ukraine war, something possible only because of its relationships with both Ukraine’s allies and Russia.

However, Türkiye’s role is complicated by internal and external challenges. Years of financial turbulence and unorthodox economic policies weakened its currency and fueled inflation, undermining some investor confidence. Externally, Türkiye faces pressure from Western partners to enforce sanctions and not become a haven for illicit flows to Russia.

Reports suggest that in 2023 the EU and US shared lists of sanctioned items to dissuade Turkish firms from re-exporting them to Russia. Meeting these demands without alienating Russia (which provides critical natural gas and tourism revenue) is no straightforward task. Any misstep could invite sanctions on itself or loss of trust from either side. Yet if it can maintain equilibrium, its ports, like Istanbul and Mersin, and logistic corridors could see sustained importance. Despite this, Marsh’s Political Risk Report notes that Türkiye is well positioned as a connector nation.

On Africa’s northwest tip, Morocco provides a case of a smaller economy leveraging connector dynamics in niche but growing areas.

Morocco is geographically positioned as a gateway between Europe and Africa, and politically it has cultivated strong ties with the EU, US, and China alike. It has a free trade agreement with the United States and an advanced trade status with the EU, even as it was the first North African country to sign on to China’s Belt and Road Initiative in 2017.

European and American firms have been investing in Moroccan solar and wind projects and in factories for electric vehicle (EV) components (like batteries), attracted by Morocco’s resources (phosphate, cobalt) and stable business climate. China, for its part, is interested in Morocco’s port of Tangier (a major container transhipment port) and in securing mineral supplies.

Morocco’s role as a connector is less about huge re-export volumes and more about positioning for future trade. In a decarbonising world, Morocco could connect resource-rich Africa with energy-hungry Europe. The country’s large lithium and copper reserves are vital for green technologies, and its political stability makes it a safer source than some other locales.

The Marsh Political Risk Report indicates that Morocco is well positioned as a connector nation. It reads, “Both the US and EU have political incentives, unrelated to existing free trade agreements, that may encourage them to grant leeway in the scale of foreign green-tech investment taking place in Morocco.” This suggests that Morocco might lock in long-term trade partnerships as a trusted intermediary (i.e., a connector) for climate-friendly supply chains.

Additionally, Morocco has become a platform for companies to produce goods for Europe using African inputs. For example, Chinese and European automakers are assembling cars in Morocco that are sold across Africa and also exported north to Europe, taking advantage of Morocco’s trade agreements.

With modest trade surpluses with Western partners (thus not a prime target for protectionist ire), and a strategic geographic location (sitting between Africa and Europe), Morocco is a strong example of a connector nation.

Being a connector nation can be a lucrative opportunity, but it comes with complex policy and regulatory side effects.

First, these countries must constantly reassure all sides of their reliability and neutralitywhich requires a careful calibration of foreign policy. For example, Hungary (an EU country acting as a connector with China) struggles to balance pro-US rhetoric with growing dependence on Chinese investment. Too much tilt one way can endanger economic ties on the other side. Connectors often pursue a diplomacy of “friends with everyone,” which can be a delicate affair when global tensions run high.

Second, connector governments face the challenge of regulatory vigilance to avoid becoming conduits for illicit or unwanted trade. As global scrutiny grows, connectors may need to enforce stricter rules on origin fraud, smuggling, or sanctioned goods passing through. For instance, Western authorities have pressed UAE and Türkiye to curb the re-exportation of high-tech items to Russia. Complying with such demands can mean short-term losses, but ignoring them risks sanctions on the connector itself.

Another issue is domestic economic policy coherence. Connector nations can experience rapid inflows of capital and shifts in their trade balance. Vietnam and Mexico, for example, have seen their trade surpluses with the US explode. Policymakers must manage these surpluses and inflows to prevent overheating or financial instability.

Currency policy is another flashpoint. Keep the currency too weak and risk accusations of unfair trade advantage; let it strengthen and potentially hurt the very export competitiveness that fuels the connector status. Vietnam has had to coordinate closely with the US to avoid being labelled a currency manipulator amid its ballooning surplus. Malaysia, by contrast, saw only limited growth in its US trade surplus, which may set it apart from peers like Vietnam and keep it out of trade skirmishes.

Connectors also need to invest in infrastructure and human capital to sustain their edge. Countries like Indonesia have the scale to be major connectors but must improve ports, logistics, and skills to truly capitalise on the diversion of trade and investment. The most successful connectors often pour resources into making it easy for global companies to operate, for instance, by building industrial parks, streamlining customs, and protecting investors. Those that do not keep up may find companies move on to the next hotspot.

Finally, there is the overarching challenge of uncertainty. Connector countries are trying to make the most of the current environment, but that environment could change quickly, particularly given the seeming revival of madman tactics in the US White House. A rapprochement between major powers could reduce the need for intermediaries, while a sharper break (like a sanctions war) could suddenly put connectors under the microscope or force them to take sides.

For larger economies with connector attributes (like India or Brazil), their own weight gives them some cushion. However, for smaller ones, policy missteps could quickly erode their hard-won gains.

The rise of connector trade nations is a symptom of a world at a crossroads. Looking ahead, two broad scenarios emerge. In one, the current connector-driven architecture persists or even expands, preventing a full rupture of the global trading system. In the other, geopolitical rifts widen, and we see a more polarised trade landscape where even indirect links are severed.

Optimists argue that connectors could help stitch the world together in spite of political tensions. These countries have a vested interest in maintaining open trade and may use their growing diplomatic heft to champion cooperation. Unlike in the original Cold War (when neutral countries had minor economic clout), today’s non-aligned nations have significant weight and can help alleviate some of the costs of fragmentation. Their active participation in global forums might keep the lines of commerce from breaking down entirely. Indeed, we are already seeing platforms where multiple blocs meet (for example, the G20, which includes many connector economies, has been pivotal in trade and finance discussions). We would then have a more networked system, where goods zigzag through friendly waypoints, but the overall volume of trade and the idea of a global market endures. Connectors may maintain or even expand their roles as links between markets, especially if policymakers see value in preserving some interdependence.

However, a more pessimistic trajectory is one of growing fragmentation. In this scenario, today’s tolerance for indirect trade wanes. Policymakers, driven by national security or domestic pressures, could impose tighter controls targeting not just rivals but also the intermediaries enabling them. If such measures proliferate, connector countries themselves could become trade pariahs in the eyes of one bloc or another. An escalation might lead to a bifurcated global economy with distinct tech standards, payment systems, and trade circuits. The IMF warns that while fragmentation so far is modest compared to Cold War levels, it could worsen considerably and prove extremely costly given how interlinked economies are today.

For now, the reality likely lies in-between. We are seeing partial decoupling with connectors picking up slack, a trend that could continue in fits and starts. Some industries (like semiconductors or telecom equipment) are being walled off between East and West, whereas others (commodities, consumer goods) still flow relatively freely, often via third parties. This persisting patchwork means global firms must navigate a more complex trade map but not an entirely shattered one.

Connectors themselves may play a peacemaker role in trade. With economies in both camps, they can ill-afford conflict and may act as intermediaries in negotiations. Some experts believe non-aligned economies could use their expanding diplomatic and economic clout to keep the world more integrated, much as Switzerland or Sweden sometimes did in earlier eras. Whether that means facilitating dialogue, offering compromise proposals in trade forums, or simply exemplifying the benefits of openness, remains to be seen.

For businesses and financial professionals, the key will be strategic flexibility. The new trade topology requires more contingency planning: understanding alternative sourcing options, monitoring political risk in connector hubs, and even adjusting currency strategies (though notably, despite geopolitical shifts, the US dollar remains dominant in trade finance, indicating that the payments architecture is slower to change). Companies would do well to map their supply chains down to second- and third-tier suppliers to see where connector countries are involved. Are those jurisdictions stable? What if new tariffs hit there? Such questions are now part of core risk management. Investors might look at which economies are poised to benefit from trade diversion but also weigh the sustainability of those gains under various geopolitical scenarios.

Finally, we must acknowledge a broader implication: global trade, while adapting, is no longer the unifying force it once was. In past decades, deep trade ties were thought to dampen conflicts (Thomas Friedman’s 1990 “Golden Arches theory” coyly posited no two countries with McDonald’s would fight a war with each other). If trade continues to fragment, that loss of interdependence could remove a key incentive for cooperation. Greater trade fragmentation may increase the risk of conflict, as a less interconnected world offers fewer disincentives to conflict.

In conclusion, connector trade nations have become pivotal characters in the unfolding story of global commerce. They are the agile middlemen of a system under strain, bringing a dose of ingenuity and resilience to global trade flows. Their rise shows how companies and countries can and will find new pathways when old ones are blocked. Whether these pathways lead to a new era of opportunity or a dead-end into deeper division will depend on choices made in Washington, Beijing, Brussels, and also in Hanoi, Mexico City, Ankara, and beyond.

Tod Burwell

Jun 06, 2025

Carter Hoffman

Jun 06, 2025

Trade Treasury Payments is the trading name of Trade & Transaction Finance Media Services Ltd (company number: 16228111), incorporated in England and Wales, at 34-35 Clarges St, London W1J 7EJ. TTP is registered as a Data Controller under the ICO: ZB882947. VAT Number: 485 4500 78.

© 2025 Trade Treasury Payments. All Rights Reserved.