Why RMB’s bet on cloud could help bridge Africa’s $120bn trade finance gap

Deepesh Patel

Jun 09, 2025

Bilal Bassiouni

Jun 12, 2025

Bilal Bassiouni

Jun 12, 2025

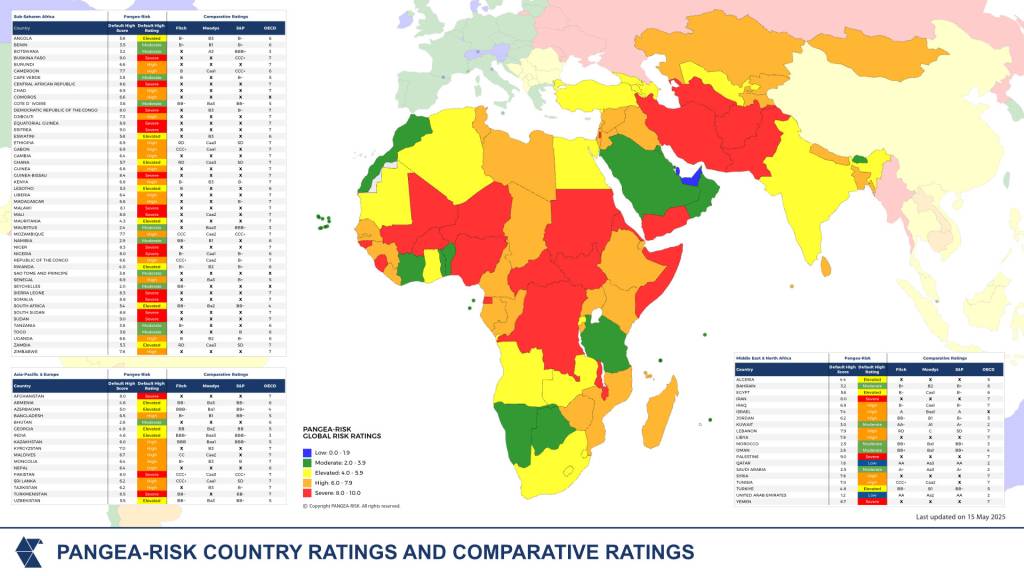

The recent credit rating downgrade of Afreximbank, a key Africa-based financial institution, has reignited concerns over elevated borrowing costs on the continent. The downgrade comes against the backdrop of a dispute among international creditors over the inclusion of loans from African multilateral institutions in sovereign restructurings. Renegotiating the terms of these debt instruments could further exacerbate existing perceptions of elevated risk in Africa, driving up sovereign borrowing costs and curtailing access to capital for development projects and trade finance, particularly during times of global economic shocks. In this context, Africa is seeking to launch its own credit ratings agency later in 2025.

On 4 June, Fitch Ratings downgraded Afreximbank’s long-term issuer rating to BBB with a negative outlook, citing heightened credit risk and perceived weaknesses in risk management. The rating action was driven by Fitch’s recalculated non performing loan (NPL) ratio of 7.1 percent, which is above its ‘high risk’ threshold, following the reclassification of loans to Ghana, South Sudan, and Zambia. This reflects the perception of heightened risk that the debt owed to Afreximbank by these sovereign borrowers may be restructured. Both Afreximbank and the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) strongly contested the rationale, asserting that the sovereign exposures are governed by treaty obligations that safeguard creditor status.

The credit rating downgrade has amplified long-standing concerns over the cost of capital for African financial institutions. Given Afreximbank’s mandate to provide support to sovereigns during periods of economic stress, any weakening of its credit profile could further constrain access to affordable financing. Indeed, a 2023 United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) study estimates the cost of credit rating idiosyncrasies in Africa to be USD 74.5 billion in excess interest and foregone funding opportunities. The study attributes this disparity more to disproportionate risk perceptions and less to economic fundamentals. These perceptions not only inflate borrowing costs but also limit the effectiveness of regional lenders in responding to debt and liquidity crises.

PANGEA-RISK examines Africa’s position in the global financial system, the debt restructuring dispute, and the case for an Africa-based credit rating agency.

Existing perceptions of elevated risk impose a premium on African sovereign borrowing. In a study titled ‘Reducing the Cost of Finance for Africa,’ the UNDP found that, even after accounting for macroeconomic fundamentals and official credit ratings, African issuers pay 2.9 percentage points more on international bond markets than similarly rated peers located elsewhere. Additionally, a study by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) published in 2023 similarly observes that Sub

Saharan African governments incur substantially higher Eurobond coupons than sovereign issuers in Latin America and Asia with comparable ratings.

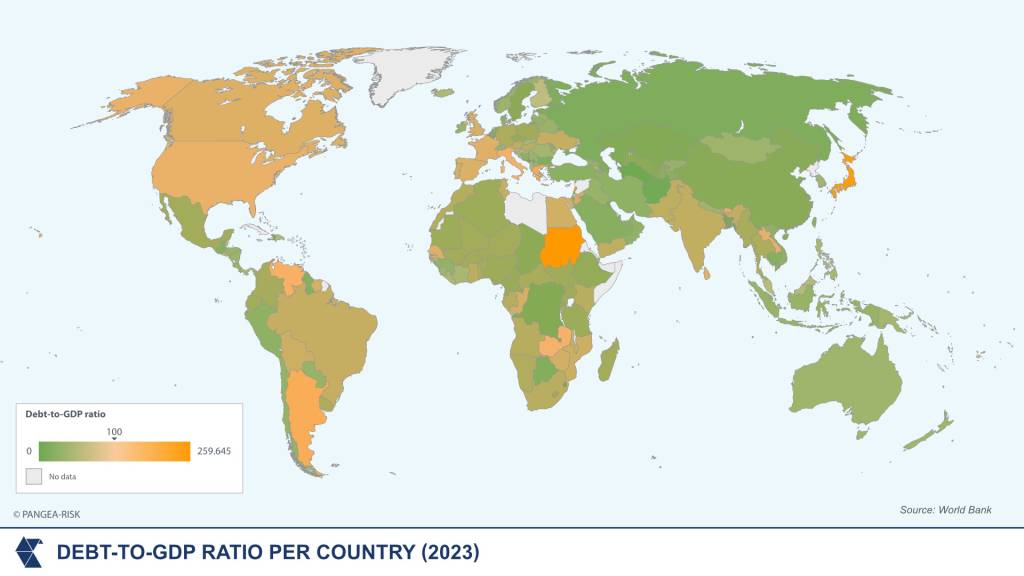

The financial toll is stark, with the UNDP estimating USD 74.5 billion due to these ‘perception premiums.’ This risk premium is at odds with Africa’s debt metrics. The continent’s total external public debt stands at under 1.5 percent of global sovereign debt, and many African countries maintain moderate debt-to-GDP ratios after years of fiscal reforms. Many African borrowers, including sovereign lenders, face double digit interest rates on debt instruments, while heavily indebted advanced economies, such as Japan and Greece, which have debt-to-GDP ratios of 216 percent and 158 percent, respectively, borrow at yields below 5 percent.

Suspicions over biased risk perceptions are driving disagreements among creditors during sovereign debt restructuring processes in Africa. African governments are under pressure to renegotiate the terms of their loans to regional multilateral lenders, such as Afreximbank and the Trade Development Bank (TDB), to exit their default status. Other creditors, including those part of the Paris Club and China, argue that these African banks must share losses as ordinary lenders, as they frequently charge interest rates on their loans comparable to commercial rates. However, these institutions assert that they lend at high interest rates largely because their own funding is expensive, which directly influences the rates they charge to sovereign borrowers.

Furthermore, both Afreximbank and TDB resist their inclusion in sovereign restructurings, citing that their founding treaties confer preferred creditor status. According to them, this provides for protection against haircuts, on par with the World Bank and the IMF. The standoff has impeded debt resolutions in Ghana, Zambia, and Malawi:

• Ghana: Ghana defaulted on its external debt in 2022. It has since restructured USD 13 billion in Eurobonds and bilateral debt. In 2024, Ghana issued new restructured bonds that included clauses ensuring no commercial creditor would be treated with preference over bondholders. Given that other creditors insist that Afreximbank is a commercial creditor, Ghana is under pressure to restructure over USD 750 million owed to the bank. Ghana has reportedly paused payments on the loan to Afreximbank.

• Zambia: Zambia defaulted on its external debt in 2020. It reached a restructuring deal with most creditors under the G20 Common Framework in 2023. Zambia owes USD 555 million to TDB and USD 45 million to Afreximbank. Zambia’s finance minister has stated that these regional banks will be treated as commercial lenders, reflecting a broad consensus among creditors over these institutions’ status.

• Malawi: Malawi has been in debt distress since 2023, and the country is struggling to conclude a restructuring. Malawi owes USD 757 million to Afreximbank and USD 145 million to TDB. The country reportedly halted normal payments to Afreximbank and TDB, which have been drawing down on a USD 190 million cash collateral account that Malawi established when the loans were contracted.

These cases highlight how higher borrowing costs in Africa and creditor disagreements compound African sovereigns’ financing challenges, which delay debt relief and, ultimately, reinforce perceptions of high risk on the continent.

Reclassifying Afreximbank’s sovereign loans as ordinary commercial debt, along with the credit rating downgrade, could erode the available mechanisms that have supported African economies during times of global economic crises. Afreximbank is one of the largest Africa-based multilateral lenders. It plays a pivotal role in ensuring that vital imports continue to flow when African sovereigns struggle to access financing from international markets. For example, it deployed a USD 3 billion Pandemic Trade Impact facility for medical supplies and a USD 4 billion Ukraine Crisis Adjustment Facility for food, fertiliser and fuel. If higher funding costs or investor caution compel the bank to curtail such programmes, African governments and the private sector may struggle to secure the hard currency needed for essential imports, deepening balance-of-payments strains during future economic shocks.

Beyond emergency lending, Afreximbank underpins key continental initiatives aimed at driving African integration and resilience. The bank’s role is anticipated to continue to grow as it provides the liquidity and guarantees for the Pan-African Payment and Settlement System (PAPSS), which settles cross-border transactions in local currencies, and helps capitalise the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) Adjustment Fund, which cushions member states against tariff-revenue losses as markets open. Higher risk premiums reduce the flexibility with which these mechanisms can be deployed. For cross-border settlement systems, this could lead to increased processing times and transaction costs. For the Adjustment Fund, higher cost of capital could narrow the fiscal space available to support tariff-loss compensation, especially in states with shallow revenue bases. Any contraction in these support lines risks delaying PAPSS deployment, raising transaction costs, and eroding confidence in AfCTA’s promise of seamless intra-African trade.

Moreover, the creditor standoff over the inclusion of Afreximbank loans in restructuring sets a precedent for other regional multilaterals. In addition to Afreximbank and TDB, other African institutions may face similar pressure to share losses on their trade finance and budget-support facilities, which could also increase their cost of capital and reduce their willingness to lend. As a result, this could further impact private investors’ perceptions towards African development banks as vulnerable to sovereign restructurings, demanding higher yields or avoiding them altogether. Such a shift would raise the cost of infrastructure and industry projects across the continent, hindering the continent’s long-term development finance capacity.

The structural exposure of African sovereigns to high funding costs and creditor misalignment has sharpened focus on the continent’s lack of independent risk assessment mechanisms. In response, the Africa Credit Rating Agency (AfCRA) is entering an advanced operational phase, with APRM targeting September for the launch of sovereign credit assessments. Institutional frameworks are reportedly finalised, with private sector stakeholders anchoring the ownership structure. This is intended to ensure both operational independence and commercial orientation. Regulatory processes are underway, and the agency’s engagement with investors and capital markets is reportedly focused on building methodological credibility.

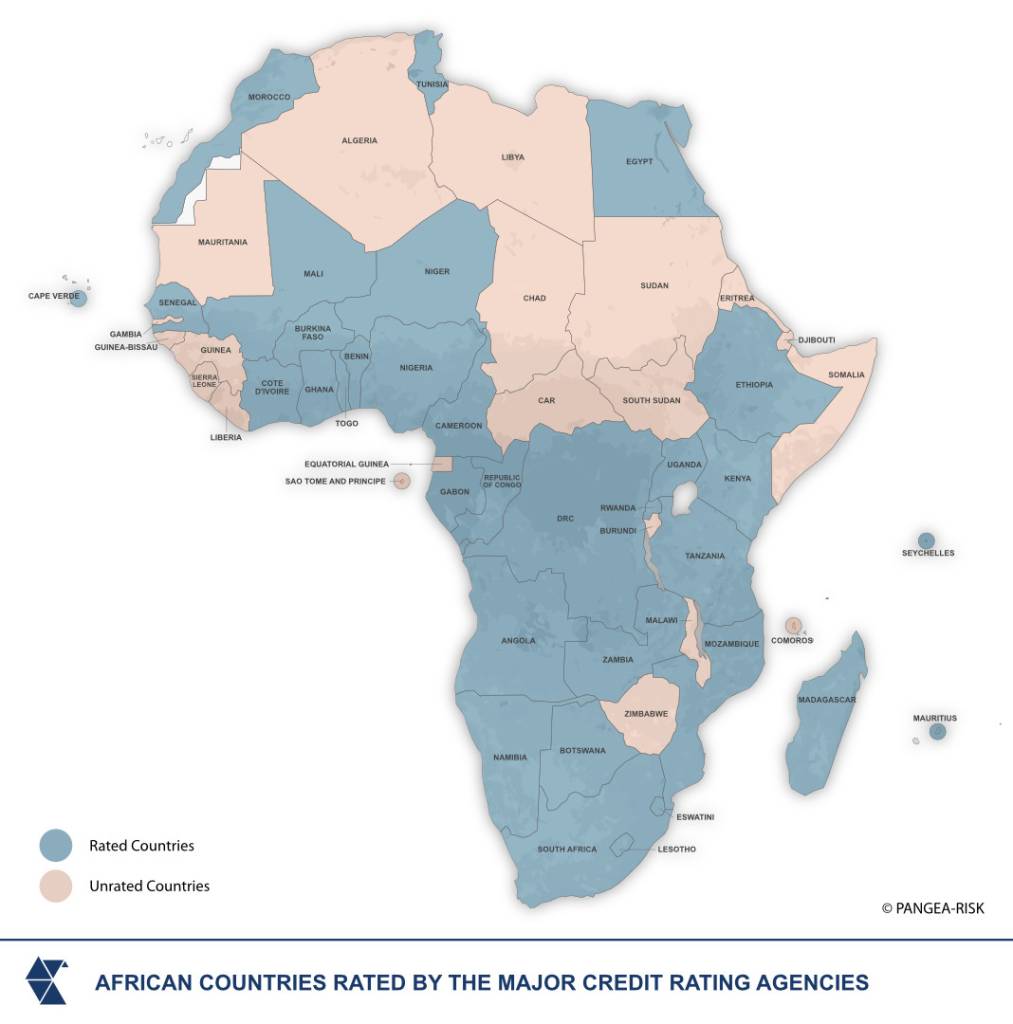

The rationale for a regionally anchored credit rating institution rests on alleged structural gaps in the continent’s credit assessment architecture and gaps in coverage. As of June, only 33 African sovereigns are rated by at least one of the incumbent global credit rating agencies. The remaining 21 countries, including Malawi, Sierra Leone, and Burkina Faso, remain outside formal sovereign rating coverage. This absence creates analytical blind spots in bond markets, restricting access to diversified funding sources and amplifying the cost of capital through proxy risk assumptions.

The gap between risk assessment and issuer context has also widened. Analytical outreach by existing agencies is often criticised as concentrated in higher-income markets, where issuer consultations are formalised and reciprocal. In lower-income African countries, sovereigns have limited opportunities to lobby and provide forward-looking fiscal or institutional clarifications before rating decisions. For example, in 2024, the French government was reportedly engaged in pre-decision briefings with one of the agencies during its review period. France’s minister of economy held sustained discussions to explain fiscal targets and structural reforms aimed at reducing the deficit. These processes remain asymmetrically available, further eroding perceived procedural parity between sovereigns of comparable formal ratings.

Nonetheless, investor caution regarding the emergence of AfCRA remains evident. Market actors continue to signal that credibility, not origin, will determine adoption. Key concerns include the methodological integrity of the ratings process, the depth of sovereign-level macroeconomic data, and the independence of risk evaluations. Where ratings are perceived as politically motivated or inconsistent with market fundamentals, adoption is likely to remain limited, and pricing benchmarks are unaffected.

AfCRA’s operational model reflects these concerns. Early indicators suggest that the intent appears to be to complement, rather than displace, existing assessments by offering broader geographic coverage and more tailored risk evaluations. The use of private capital in the agency’s ownership is intended to protect it from sovereign influence, while also aligning it with market expectations regarding transparency and disclosure.

The extent to which AfCRA closes the gap between risk perception and debt fundamentals in Africa will depend less on institutional identity than on whether the ratings are interpreted as analytically rigorous, methodologically sound, and procedurally transparent. Early assessments will serve as market signals and also as indicators of the agency’s viability in influencing investor models and sovereign funding strategies.

Afreximbank’s credit downgrade reflects a shift in how multilateral exposures to distressed African sovereigns are treated in credit models. The recalibration of its non-performing loan ratio above the high-risk threshold was triggered by the reclassification of loans to Ghana, Zambia, and South Sudan. These exposures were previously treated as treaty-protected. The reclassification introduces uncertainty for other sovereign-linked facilities, particularly in jurisdictions where restructuring discussions remain unresolved or opaque.

The downgrade creates direct cost implications for syndicated trade and commodity finance structures anchored by Afreximbank. Rising funding costs will result in less favourable terms for counterparty institutions that rely on their balance sheets for liquidity backstops or political risk mitigation. For borrowers, this may affect the pricing of commodity-backed credit lines or delay disbursements where transactions require risk participation from the downgraded institution. For lenders, reduced credit quality raises capital provisioning requirements, particularly in projects where Afreximbank provides partial guarantees or structuring support.

Sovereign restructurings are reshaping expectations regarding burden-sharing among creditors. In Ghana and Zambia, the push for Afreximbank’s classification as a commercial creditor introduces procedural uncertainty for debt resolution. If multilateral African institutions are grouped with commercial lenders, it could blur the distinction between development finance and commercial lending. This could impact the structuring of future budget support operations and affect how repayment assurances are treated under both local and international processes. Institutions involved in resource-backed lending or trade credit facilities will need to reassess how sovereign credit events impact recovery pathways for non-sovereign instruments that are indirectly exposed through central government guarantees.

Export credit agencies with exposure to sovereign-linked African projects face a more complex risk environment. Where Afreximbank acts as a co-financier, liquidity provider, or counterparty, the downgrade may necessitate revisions to internal risk classifications. This could influence future cover limits or require adjustments to risk-sharing ratios on syndicated projects and trade deals. However, the impact will not be uniform. The degree of recalibration will depend on the specific role Afreximbank plays in transactions and the jurisdictional context of each operation.

The credit rating asymmetry between African sovereigns and similarly rated peers in other regions introduces embedded cost inefficiencies. Even where debt-to-GDP ratios are moderate, African issuers incur interest rates well above global averages. This constrains the ability of domestic financial systems to effectively intermediate capital. The persistent exclusion of 21 African countries from international credit ratings limits their access to diversified borrowing. In these cases, risk pricing depends on proxies, which increases volatility and reduces clarity for trade and capital planning.

The planned operationalisation of AfCRA may address analytical gaps, but it will only influence market conditions if the agency’s outputs are integrated into commercial pricing models and accepted within the frameworks used by export credit agencies (ECAs) and institutional lenders. Until then, the broader structural cost of fragmented credit visibility will persist across sovereign and non-sovereign African borrowers.

Deepesh Patel

Jun 09, 2025

Trade Treasury Payments is the trading name of Trade & Transaction Finance Media Services Ltd (company number: 16228111), incorporated in England and Wales, at 34-35 Clarges St, London W1J 7EJ. TTP is registered as a Data Controller under the ICO: ZB882947. VAT Number: 485 4500 78.

© 2025 Trade Treasury Payments. All Rights Reserved.