SaturnX secures $3 million to scale stablecoin infrastructure for cross-border remittances

Carter Hoffman

Jun 20, 2025

Carter Hoffman

Jun 20, 2025

Carter Hoffman

Jun 20, 2025

At a time when the world faces intensifying geopolitical rifts, rising protectionism, and weakening multilateral frameworks, the latest World Investment Report from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) offers a sobering barometer of global capital flows. Despite modest headline figures, the report reveals that international investment is faltering, and in the areas that matter most.

Global foreign direct investment (FDI) flows declined 11% in real terms in 2024, continuing a downward trend that UNCTAD describes as “persistent fragility.” Investment into large-scale infrastructure, industrial projects, and Sustainable Development Goal (SDG)-aligned sectors has slowed to a crawl. At the same time, digital investment – led by semiconductors and data infrastructure – may be the sole bright spot. Yet even this growth risks entrenching divides rather than bridging them.

Released ahead of the Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development, the World Investment Report 2025 reflects today’s disjointed investment landscape and provides a roadmap for reshaping it.

Below, we unpack the key findings.

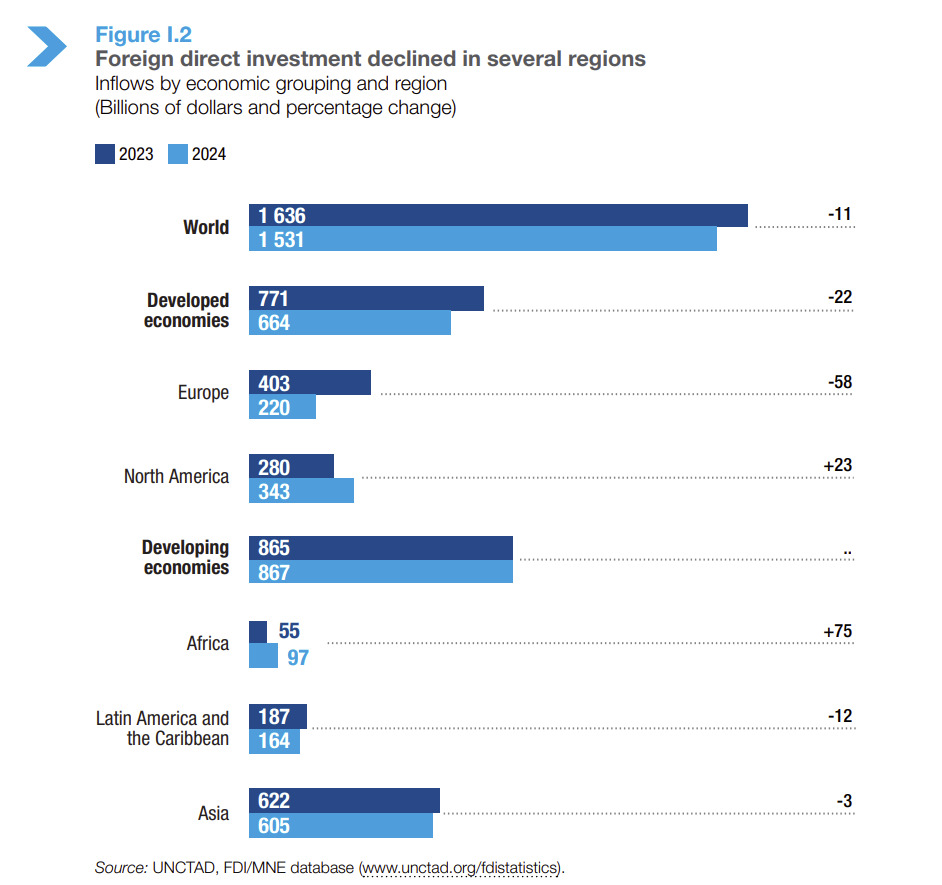

In nominal terms, global FDI increased slightly in 2024, from $1.45 trillion to $1.51 trillion. But this headline figure is misleading. Once volatile conduit flows, particularly those routed through financial centres in Europe, are removed, the true picture reveals an 11% year-on-year decline. That is the second consecutive year of double-digit contraction in real terms, leaving FDI increasingly out of step with other macroeconomic indicators like GDP and trade volumes.

Regional trends are more mixed. European inflows declined by 58%, driven in part by corporate restructuring and policy uncertainty, while North American inflows rose by 23%, buoyed by high-tech and clean energy investment in the United States. FDI to developing countries remained broadly flat at $867 billion, but flows were highly concentrated, with just ten nations accounting for three-quarters of all developing-country inflows.

Africa saw the most dramatic percentage increase (75%), although this was skewed by a single $35 billion megaproject in Egypt. Excluding that project, the region still grew by 12%. This level of concentration can itself be worrying. Greenfield project announcements in Africa, for instance, actually declined 5% year-on-year.

Perhaps most concerning is the outlook for 2025. Early data from the first quarter shows record lows in cross-border deals and new project announcements. Investor sentiment has soured, and policy volatility (including the fresh wave of tariff escalations) has cast a long shadow over global investment prospects.

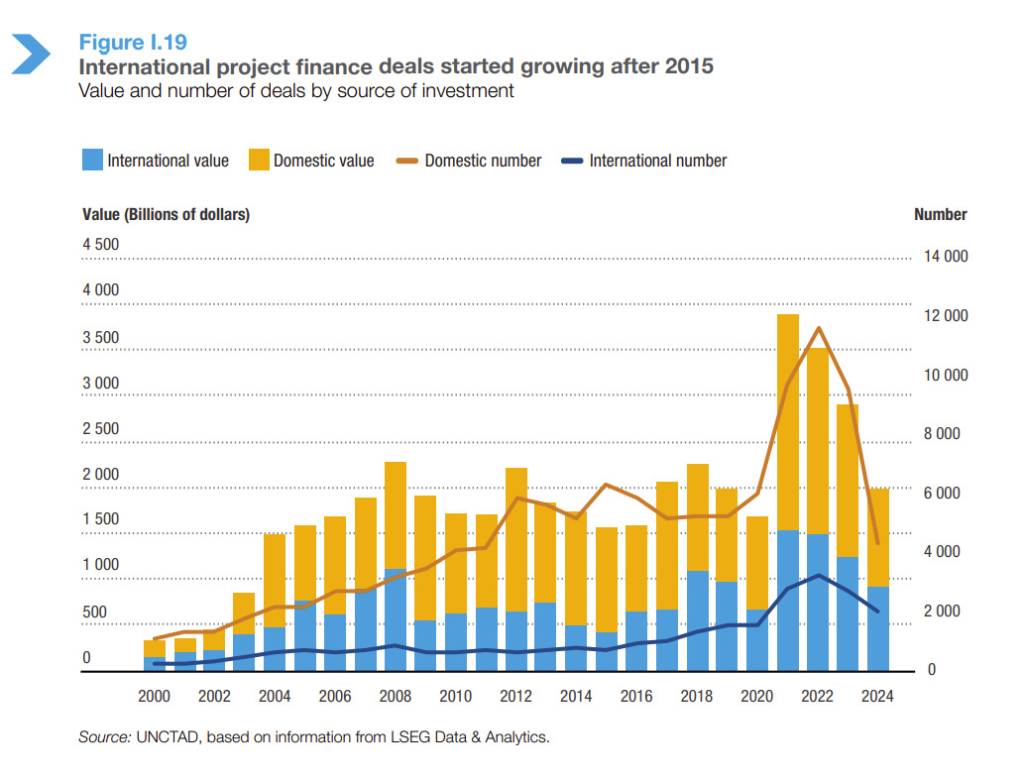

Few areas illustrate the depth of the investment crisis more starkly than the decline in international project finance (IPF), which is a key mechanism for funding infrastructure in developing economies. Between 2021 and 2024, the value of IPF deals plummeted by more than 40%, with a further 26% decline recorded in 2024 alone. Rising borrowing costs, currency risks, and tightening financial conditions have all played a role, leaving capital-intensive projects, especially in least developed countries (LDCs), in jeopardy.

This contraction has had profound knock-on effects on SDG-aligned sectors. Investment in renewable energy fell 27% in value terms, despite global commitments to a just energy transition. Agrifood systems (-19%), water and sanitation (-30%), and transport infrastructure (-67%) also recorded sharp declines. The only SDG sector to buck the trend was healthcare, which saw a 25% increase in project value, albeit from a low base.

These figures represent missed opportunities for progress. In a world increasingly committed, at least rhetorically, to inclusive and sustainable development, the data suggest that capital is flowing in the opposite direction. The gap between SDG ambition and investment reality is widening.

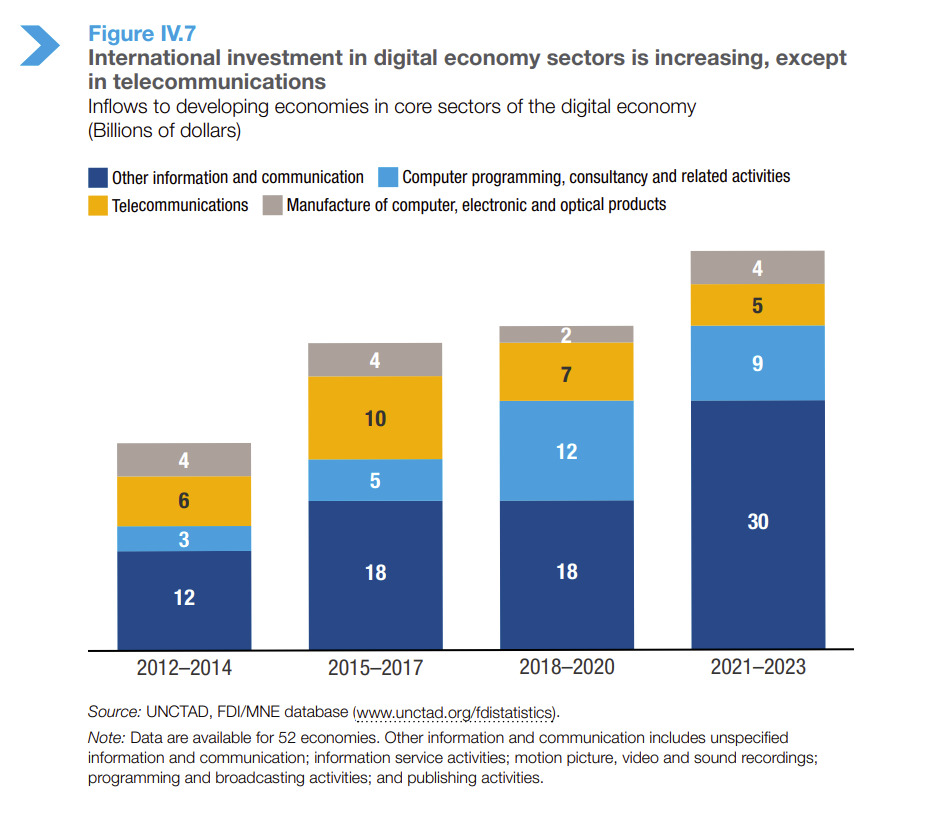

In stark contrast to the broader downturn, digital sectors continued their run as a powerful growth engine in 2024. Greenfield investment in digital industries more than doubled, with semiconductor-related projects alone rising by 140%. Four of the ten largest greenfield projects globally were in chip manufacturing, three of which are located in the United States. Investment in data centres and AI infrastructure has risen sharply alongside demand for processing power and strategic interest in digital sovereignty.

Technology firms now account for more than 20% of the revenues of the top 100 multinational enterprises (MNEs). Much of this growth has been underpinned by government policy. Industrial strategies, such as the CHIPS Act in the US, are explicitly reshaping capital allocation decisions.

Private capital is following suit. Sovereign wealth funds, public pension funds, and private equity investors are increasing allocations to digital infrastructure, viewing it as a stable, inflation-resilient asset class. While total FDI flows are shrinking, digital projects are expanding, gaining a larger share of global investment.

But there is a caveat. Over $500 billion in digital investment has flowed into developing countries over the past five years, yet the vast majority has gone to a narrow group of middle-income economies. Structurally weaker countries (particularly LDCs and small island developing states) remain on the margins. Without targeted support and integrated digital-industrial strategies, the digital divide may deepen rather than close.

The report’s authors point to a new era of “policy-driven fragmentation,” in which governments are actively redirecting investment decisions.

Nowhere is this more visible than in the recent wave of tariff measures. As of May 2025, the United States has imposed 10% baseline reciprocal tariffs on imports from 59 countries, with additional restrictions on Chinese goods. These measures, coupled with outbound investment screening and industrial reshoring incentives, are recalibrating global supply chains and multinational firms are adapting accordingly.

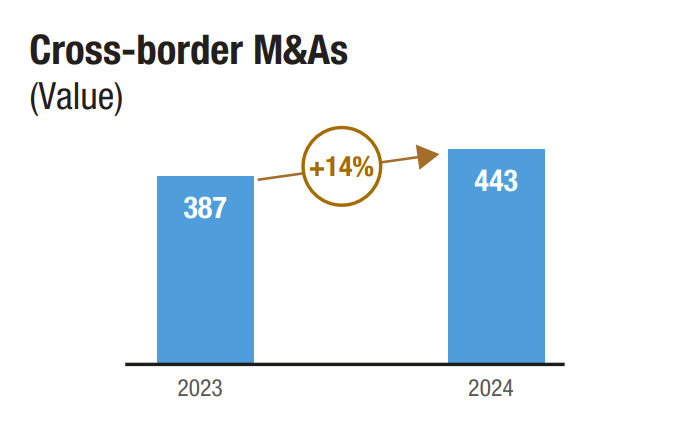

Cross-border M&A rose 14% in 2024, but a growing share of acquisitions are domestic or regional in scope, in line with the shift toward nearshoring. Strategic sectors (particularly electronics, chemicals, and renewable energy) are undergoing structural realignment, often guided more by geopolitics than by comparative advantage.

The implications of this for developing countries are mixed. While some may benefit from the reconfiguration of production networks, others risk being bypassed entirely.

The digital economy may be booming, private capital mobilising, and technology-led investment reshaping global value chains, but, sustainable infrastructure is being starved of funding, and FDI is becoming more fragmented, selective, and politicised.

The challenge now is to reverse the divergence. A thriving digital economy can be a driver of inclusive growth only if its benefits are more widely distributed. Infrastructure investment, particularly in SDG sectors, must be revitalised through coordinated public-private action and multilateral lending reform.

As the international community prepares for the upcoming Fourth Conference on Financing for Development, the stakes are high. Investment flows are a reflection of our collective priorities, and if those priorities are to include sustainability, equity, and resilience, then policy frameworks and capital markets must be realigned accordingly.

To explore the full findings, data, and policy recommendations, read the UNCTAD World Investment Report 2025.

Carter Hoffman

Jun 20, 2025

Devanshee Dave

Jun 20, 2025

Trade Treasury Payments is the trading name of Trade & Transaction Finance Media Services Ltd (company number: 16228111), incorporated in England and Wales, at 34-35 Clarges St, London W1J 7EJ. TTP is registered as a Data Controller under the ICO: ZB882947. VAT Number: 485 4500 78.

© 2025 Trade Treasury Payments. All Rights Reserved.