Resource-rich states use minerals for diplomatic leverage amid great power rivalry

Bilal Bassiouni

May 16, 2025

Yuichiro Akita

May 16, 2025

Yuichiro Akita

May 16, 2025

At the Berne Union Spring Meeting in Dubrovnik (May 2025), export credit agencies (ECAs) and insurers convened against a backdrop of war, sovereign debt concerns, climate threats and technological change. Naturally, “Resilience” became the guiding theme, as global trade norms are shifting from pure economics to geopolitics.

In an interview with Trade Treasury Payments (TTP), Yuichiro Akita, President of the Berne Union, discussed how ECAs must adapt strategically to this new environment. Key priorities include supporting climate and clean-tech projects even in high-risk markets, shoring up supply chain resilience amid geopolitical fragmentation, deepening collaboration with development finance institutions (DFIs) through blended finance, innovating in underwriting and risk management post-pandemic, and recalibrating risk appetite to enable critical projects.

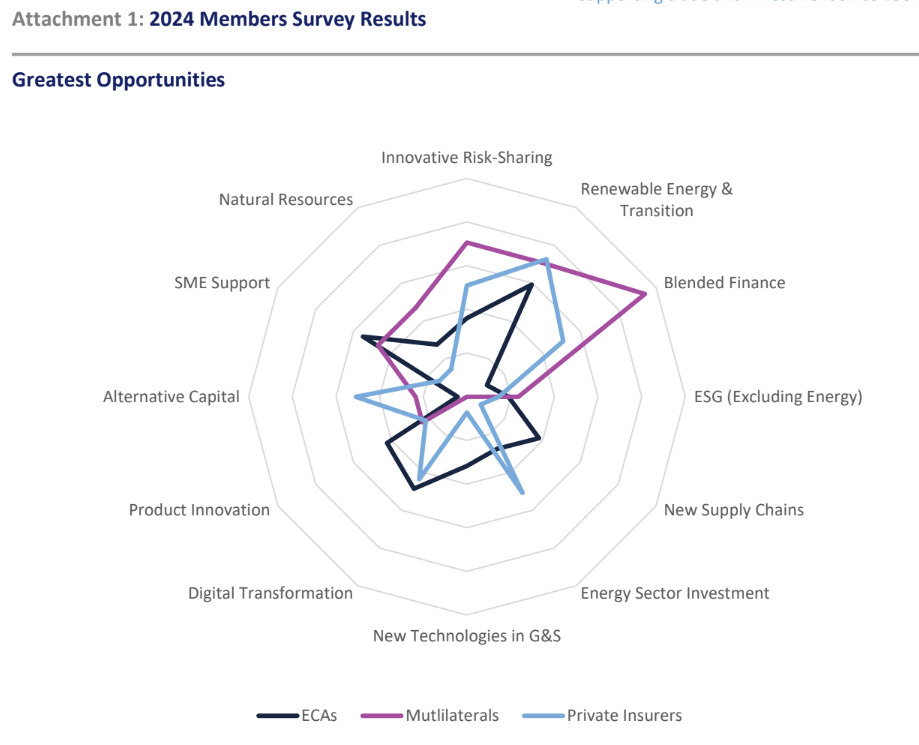

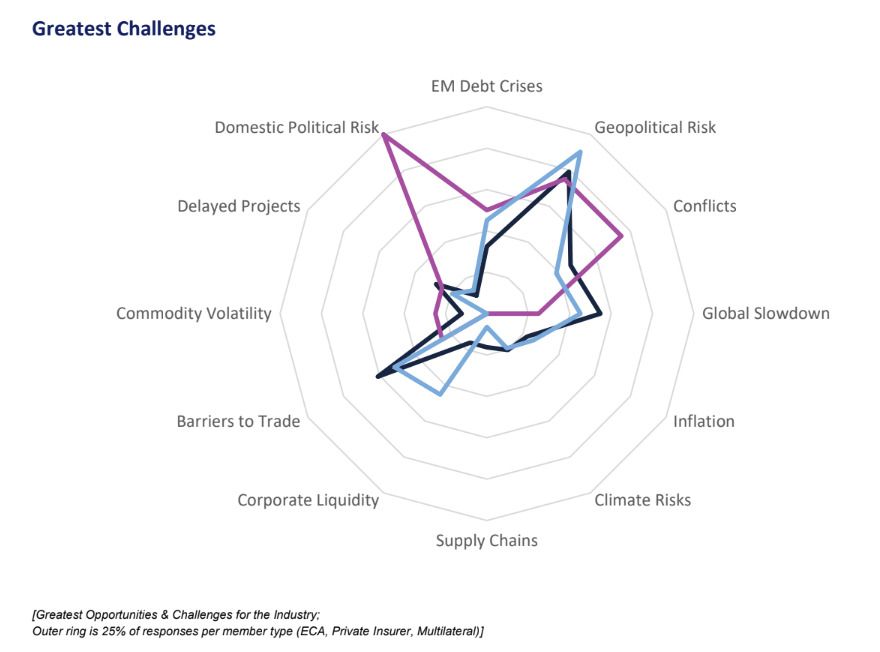

These themes, echoed in industry reports and surveys, rank among the top opportunities and challenges facing the export credit industry today.

ECAs are increasingly steering support toward renewable energy, clean infrastructure and emerging green technologies. Recent OECD export credit reforms explicitly incentivise climate-friendly and green projects with longer repayment terms and lower premiums.

This policy shift is a significant milestone on the path to boosting trade finance alignment with global climate objectives, as nearly half of the emissions cuts needed for net zero rely on technologies still in prototype or demonstration phases. Naturally, these newer technologies carry higher commercial risk, however ECAs are in a unique position to be able to promote them by extending cover where many other insurers may not be willing.

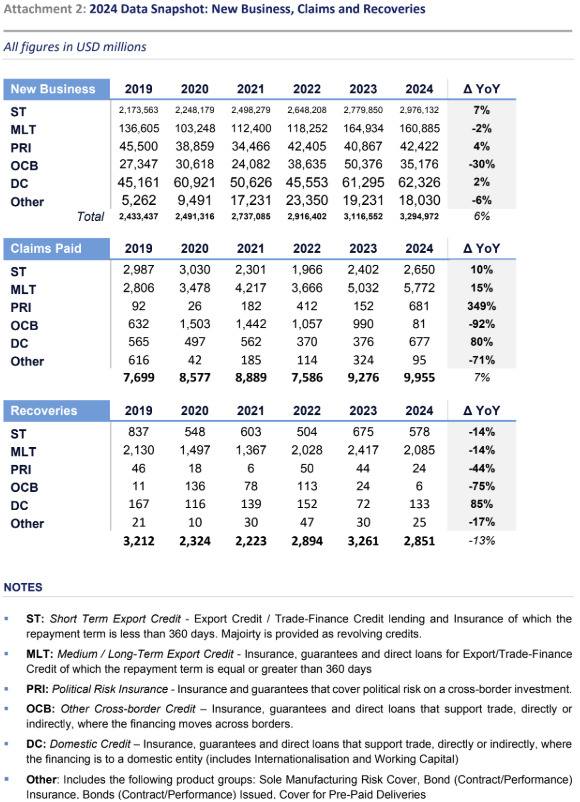

Akita said, “Since the BU began tracking sector underwriting in 2019, new commitments towards renewable energy have increased steadily, and amounted to $15 billion in 2024 (2.5 times the level of 2019). In the same time, we have seen a corresponding decrease in new commitments towards traditional energy production.”

A challenge remains in defining what exactly qualifies as “green”. An analytical discussion will note concerns that loose definitions could allow support for fossil-fuel-linked projects under a green label, versus a stricter focus on truly clean tech.

Geopolitical rifts and trade tensions are re-drawing supply chains. Amid tariffs, sanctions, and war, companies are pursuing “friend-shoring” (the practice of relocating production to politically allied or stable nations) to reduce vulnerability. The Berne Union’s members report that while awareness of such shifts is high, most ECAs are still evaluating impacts before overhauling their strategies.

Traditionally focused on exporters and overseas buyers, ECAs are now expanding support to critical links upstream and downstream. For instance, many are extending cover to exporters’ suppliers to prevent disruptions. This means providing working capital guarantees, insurance for pre-shipment finance, and coverage for domestic suppliers. The Berne Union’s data show ECAs have significantly grown such “atypical” support, contributing to a 54% rise in non-traditional commitments since 2019.

Akita said, “From a broader perspective, rising geopolitical risks have certainly increased the demand for PRI. At the same time, they have also served as a catalyst for innovation on the supply side—prompting providers to find new ways to manage high-risk portfolios, control concentration risk, and develop new underwriting approaches.”

ECAs and trade insurers are also being forced to respond to buyers that are diversifying their sources and governments that are seeking self-reliance in critical sectors (such as semiconductors or medical supplies). New supply chain financing programmes and credit facilities have been set up to fortify crucial imports and exports against shocks.

Heightened geopolitical risk, however, is increasingly becomming a core underwriting concern. A survey from the Berne Union identified political upheavals, protectionism, and conflict as top industry worries, alongside a surge in claims on trade credit insurance due to war and sanctions.

Given this, it seems that many ECAs are bearing the fallout of the shift from economics to politics as the force behind trade trends, something that is forcing them to adjust pricing and cover terms for transactions in geopolitically sensitive regions, and coordinate with national trade strategies.

Large-scale projects in emerging markets often exceed the capacity or mandate of any single institution. There is growing recognition that ECAs, multilateral development banks (MDBs), and development financial institutions (DFIs) must pool their tools under blended finance frameworks.

To see a prime example of blending finance, we can turn to what happened during the COVID-19 pandemic. In that time, ECAs, MDBs, private banks and insurers came together to finance vaccine production and protect trade in critical goods. Blended structures combined ECA guarantees with DFI loans and private capital, sharing risks to get urgent projects off the ground. Each actor brought something to the table (e.g., concessional funding, guarantees, local knowledge), enabling outcomes (e.g., global vaccine supply chains) that none could achieve alone. This collaborative model is now being extended to climate and infrastructure deals.

Akita said, “I believe BU members have been engaged in blended finance for a long time. By providing insurance and guarantees to private financial institutions, they’ve enabled the realisation of national policy goals. In return, the private sector has provided financing, often at lower interest rates than without its cover.”

Such innovation aims to crowd in private investors under the umbrella of ECA risk cover, multiplying the available financing for high-risk greenfield projects. The OECD and World Bank have published guidance on using concessional funds to mobilise private investment, and G20 communiqués regularly call for MDBs and ECAs to coordinate on infrastructure finance.

Closer ECA-MDB cooperation is a logical evolution. Export financiers bring risk mitigation expertise, while development banks bring patient capital and development focus. Together, under structured deals, they can tackle projects (ranging from renewable energy in Africa to digital infrastructure in Asia) that would otherwise be too risky or uneconomical.

Systemic shocks, especially the pandemic, have highlighted the value of technology in underwriting. Many ECAs are investing in digital platforms to speed up application processing and risk assessment. For instance, export credit agencies are deploying AI and data analytics to model complex risks and to make underwriting decisions more quickly.

Facing more frequent systemic events (i.e., war, supply chain collapse, trade disruptions), ECAs are also innovating how they share and distribute risk. Co-insurance and reinsurance arrangements have expanded as public insurers are ceding more risk to private reinsurers to stretch their capacity.

According to Swiss Re, such partnerships give ECAs access to advanced risk modelling and underwriting tools, improving their ability to price evolving risks. Some ECAs have created new contingency products (for example, short-term credit insurance for sudden supply shocks, or insurance for non-payment due to government lockdowns) as part of a more resilient underwriting toolkit.

ECAs are increasingly stress-testing their portfolios against extreme scenarios and adapting their risk frameworks accordingly. The industry is moving toward pricing systemic risk more explicitly and building capital buffers so that it can keep supporting exporters when the next crisis hits.

Perhaps the most consequential shift in the ECA space is a recalibration of risk appetite. ECAs are traditionally cautious, mandated to cover “safe” bets with reasonable assurance of repayment. Yet the pressing demands of today often fall outside existing risk comfort zones.

There has been a divergence between private insurers and ECAs in risk tolerance. Since 2022, as geopolitical risks mounted, private credit insurers became more risk-averse, anticipating a wave of claims from war and insolvencies. Public ECAs, by contrast, have largely held firm or even indicated plans to increase their risk appetite to support trade through the uncertainty.

This counter-cyclical role (i.e., stepping in when private capacity shrinks) is fundamental to export finance; however, ECAs may need to stretch even further on risk in the current climate, of course with prudent risk management, to ensure vital projects proceed.

ECAs willing to increase their risk appetite for complex new technologies or business models that can significantly shape global outcomes. For example, financing a first-of-its-kind clean tech project or entering a post-conflict market entails higher default risk, but also high developmental payoff.

Akita said, “In the ECA industry, when we talk about ‘risk appetite,’ we’re really asking: are we willing to take on more risk than usual to achieve policy goals or create real value? ECAs have operated under the OECD guidelines for a long time, but maybe we’re now trying to pour new wine into old wineskins.”

Recalibrating risk appetite does not imply being reckless. This is because ECAs are simultaneously enhancing their risk analytics and lobbying for government backstops and guarantees for exceptionally risky initiatives (such as greenfield projects in low-income countries) to ensure they can take more risk without jeopardising financial stability. Slightly higher risk appetite in service of national and global priorities, paired with innovative risk mitigation (insurance, guarantees, reinsurance) can help keep losses manageable.

ECAs are not abandoning prudence, but rather are broadening their mission from traditionally insuring safe exports to actively enabling the trade and investments that will define the next decades.

Ultimately, recalibrating means ECAs accept that to remain relevant, they must sometimes venture outside their comfort zone. The risk of inaction may outweigh the risk on their balance sheets. Export finance is becoming more of a policy tool for climate action, economic security, and development co-operation, demanding greater partnership and a long-term view on risk and reward.

But what does this all mean for trade professionals? Expect export finance to be more flexible and mission-driven. ECAs will likely offer more blended products, cover more unconventional risks, and engage earlier in project planning. For exporters and banks, this may open new opportunities as financing for projects once deemed too risky might now be feasible with ECA backing.

As Akita said, “Being able to serve as Berne Union President at such a pivotal time is something I feel very fortunate and excited about. The steps I take might be small, but I hope to contribute in a meaningful way to help move the industry forward.”

Bilal Bassiouni

May 16, 2025

Trade Treasury Payments is the trading name of Trade & Transaction Finance Media Services Ltd (company number: 16228111), incorporated in England and Wales, at 34-35 Clarges St, London W1J 7EJ. TTP is registered as a Data Controller under the ICO: ZB882947. VAT Number: 485 4500 78.

© 2025 Trade Treasury Payments. All Rights Reserved.